Revisiting FDA's proposed menthol ban

An "important step toward reducing disease inequities in the US"?

In April 2022, the FDA announced proposed rules to prohibit menthol cigarettes. The proposed rules have two main goals (emphasis mine):

The proposed rules would help prevent children from becoming the next generation of smokers and help adult smokers quit,” said Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra. “Additionally, the proposed rules represent an important step to advance health equity by significantly reducing tobacco-related health disparities.

The FDA explained what they mean by health equity in this context:

In 2019, there were more than 18.5 million current menthol cigarette smokers ages 12 and older in the U.S., with particularly high rates of use by youth, young adults, and African American and other racial and ethnic groups.

The health equity argument

When reporting on the proposed bans, most news organizations focused on the health equity goal in their reporting. They make the following points, either explicitly or implicitly:

Black smokers are more likely to smoke menthols than other smokers

Menthol makes it easier to start and continue smoking

Blacks have higher rates of smoking-related illnesses and deaths

Higher rates of illnesses among Blacks are due to menthols

Therefore, banning menthols will reduce the discrepancy in health outcomes

Black smokers are more likely to smoke menthols

CNN:

About 30% of White smokers choose menthols, but they are the cigarette of choice for nearly 85% of smokers who are Black.

Today, more than 85 percent of Black smokers choose menthol cigarettes — almost three times the proportion for White smokers.

Public health experts say the proposal could save hundreds of thousands of lives, especially among Black smokers — 85 percent of whom use menthol products.

AP:

Menthols are used by 85% of Black smokers.

NPR:

Rates of menthol cigarette use were higher among young people and in Black communities.

Menthol makes it easier to smoke

The Washington Post:

Studies have shown that menthol, which has a minty taste and provides a cooling sensation, makes it easier for young people to start smoking by masking throat irritation caused by cigarettes.

The New York Times:

Menthol … is added to cigarettes to make smoking less harsh, providing a cooling sensation in the throat and making the experience more appealing.

AP:

Menthol’s cooling effect has been shown to mask the throat harshness of smoking, making it easier to start and harder to quit.

Blacks have higher rates of smoking-related illnesses

The Washington Post:

African Americans die of tobacco-related illnesses, including cancer and heart disease, at higher rates than other groups.

The New York Times:

African American men have the highest rates of lung cancer in America, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Menthol is responsible for higher rates of illnesses and deaths

CNN:

“For decades, tobacco companies have intentionally pushed menthol cigarettes to hook young people on their deadly products and implemented racist marketing practices to intentionally target Black Americans; the resulting health consequences have been devastating,” Dr. Julie Morita, executive vice president at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation advocacy organization, said in a statement.

The New York Times:

Public health experts say menthol cigarettes have been heavily marketed to Black people, to devastating effect

AP:

African American groups … say menthol has led to lower quit rates and higher rates of death among Black people

Banning menthols will reduce the discrepancy in health outcomes

The Washington Post:

“This is a giant step forward” in decreasing health disparities, said Carol McGruder, co-chair of the African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council.

NPR (emphasis mine):

Erika Sward, assistant vice president of national advocacy for the American Lung Association, told NPR that the measure is “a big deal” and that rules to ban menthol are overdue. “It will save lives, especially in Black and brown communities in the United States, and it will reduce youth smoking,” Sward said.

AP:

“Black folks die disproportionately of heart disease, lung cancer and stroke,” said Phillip Gardiner of the African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council. “Menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars are the main vectors of those diseases in the Black and brown communities, and have been for a long time.”

Would banning menthols really reduce the discrepancy in health outcomes?

The argument sounds very convincing until we look at the data: Smoking prevalence is actually lower among Black adults than White adults and tobacco usage is actually lower among Black youth than White youth. It is unclear to me that menthols are causing higher rates of smoking-related illnesses in Black populations and that banning them will reduce the discrepancy in health outcomes.

Black adults smoke at lower rates than Whites

The reporting from most news media gives the impression that Black people are more likely to smoke than White people. After all, if menthol makes it easier to start and continue smoking and Black smokers are three times more likely to smoke menthols, it is easy to think that more Black people smoke. To the best of my knowledge, AP is the only major media that reported on smoking prevalence:

More than 12% of Americans smoke cigarettes, with rates roughly even between white and Black populations.

This is pretty accurate. Actually, even more accurate would be to say that the rate is lower among Blacks. In 2021, according to the adult tobacco product use analysis of the National Health Interview Survey, 11.5% of Americans smoked cigarettes. Among Blacks the rate is 11.7% and among non-Hispanic Whites the rate is 12.9%. You read that correctly: Blacks were 1.2 percentage points (or about 10% in relative terms) less likely to smoke than non-Hispanic Whites in 2021.

(The confidence intervals might seem large but the results are consistent year after year after year — Black adults smoke at lower rates than White adults.)

The data is actually even more extraordinary than it looks at first sight. We know that smoking rates are negatively correlated with income and education. For instance, the same survey shows that 18% of low income Americans smoke versus only 7% of high income Americans, and that 31% of GED holders smoke versus only 3% of graduate degree holders. As we all know, on average, Blacks have lower income and lower education attainment.

Simply based on correlation between smoking, on one hand, and income and educational attainment, on the other hand, one would actually expect Blacks to smoke at higher (perhaps much higher) rates than Whites.

Black youth use tobacco products at lower rates than White youth

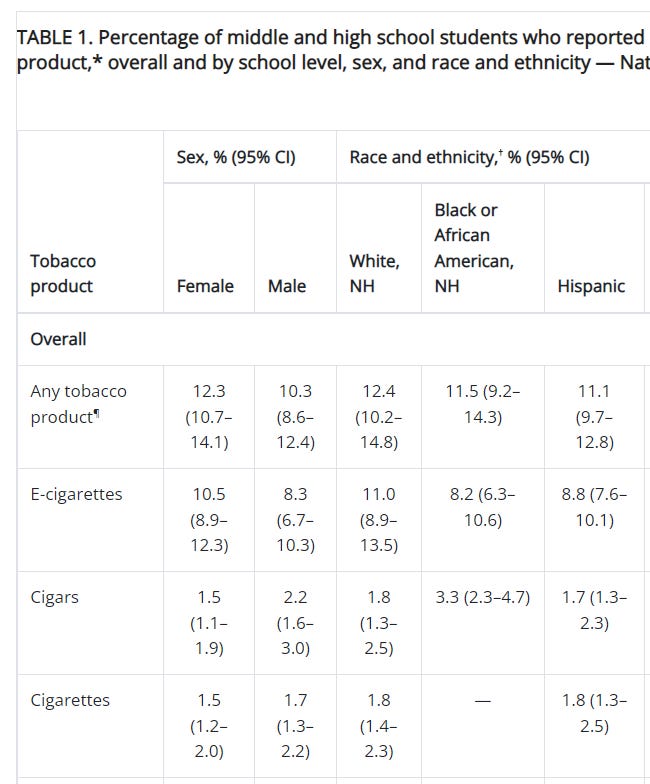

Not only do Black adults smoke at lower rates than White adults, but Black youth also use tobacco products at lower rates than White youth. From the 2022 National Youth Tobacco Survey:

Whereas 12.4% of White middle and high schoolers have used any tobacco product during the 30 days preceding the survey, only 11.5% of Black youth has done so. I’m reporting on tobacco use rather than the more specific cigarette smoking because cigarette smoking rates are now fortunately so low among middle and high schoolers (fewer than 2% have smoked cigarettes in the 30 days leading to the survey) that Black youth cigarette smoking rate is not reported in the table above.

Wrapping up

From a statistical point of view, it seems strange to claim that menthols cause more smoking-related illnesses and deaths in Blacks or to predict that Black smoking rates would decrease if menthols were illegal. There might be sensible explanations why I’m wrong and I’d be happy to read your thoughts in the comments.

I want to leave you with a sentence from a Washington Post editorial that made me chuckle (emphasis mine):

A new study in the journal Tobacco Control found that a U.S. menthol ban could persuade 1.3 million smokers to quit, including 381,272 Black smokers.

One has to admire the precision!